THE END OF ROMANTICISM

Click on the thumbnails to enlarge them and switch to full screen mode.

The End of Romanticism [FR]

Galerie Janine Rubeiz presents The End of Romanticism, a group exhibition featuring Gregory Buchakjian, François Sargologo, and Hanibal Srouji. The three artists reunite in the same space a decade after Pellicula. In their previous collaboration, they questioned the ways in which images are made and preserved, through works that blurred the boundaries between the media of painting, photography, drawing, and writing. While The End of Romanticism further intensifies this intermingling of disciplines, the first thing that might intrigue visitors is its title, an anachronism in itself. It is widely accepted that Romanticism was an artistic, literary, and musical movement that emerged in the late 18th century and faded, at least as a dominant phenomenon, by the mid-19th century, giving way to Realism.[1] So why, in 2025, announce the end of something that ended nearly two centuries ago? Are these artists, one of whom is an associate professor of art history, so ill-informed? Do they believe the audience is misled? Or are they trying to question something? The answer might lie in what they are willing to show.

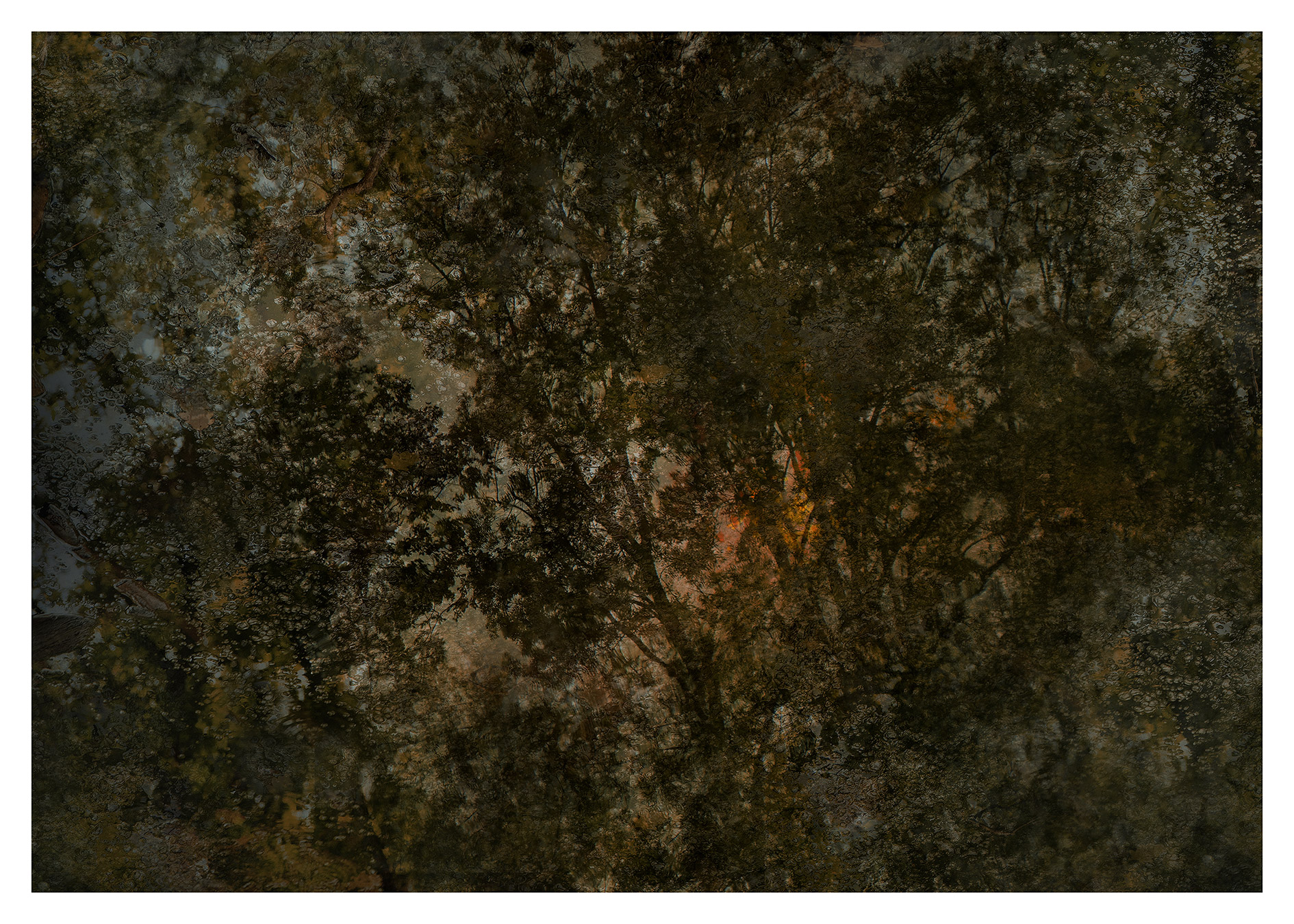

Sargologo’s photographic scenes, characterized by the omnipresence of exuberant nature, bear the same name as the exhibition. These panoramas, akin to a state of « waking dreaming », reflect a body of work inspired by the realm of oneirism and romantic parody. However, Romanticism is neither Realism nor Naturalism; it undoubtedly acts to distance itself from reason and objectivity, at the risk of falling into the Platonic simulacrum, a mere imitation of what it claims to represent.[2] In The Logic of Sense, Gilles Deleuze had already proposed rehabilitating the simulacrum by attributing to it an intrinsic value independent of what it falsely represents. In Simulacra and Simulation, Jean Baudrillard takes the idea even further; for him, the simulacrum is no longer about parody or falsification but about « substituting the signs of the real with the real itself. »[3]

Sargologo’s photographic scenes are no longer intended to paint an accurate portrait of nature, which becomes no more than a pretext for something else. Sargologo thus goes beyond Romanticism, surpassing it and pushing it to the limit, to the point of becoming a caricature of himself.

This body of work evokes nature at its apotheosis, heralding something yet to come. It calls upon the sublime in the sense that Edmund Burke described in A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, a delightful horror, i.e., a feeling that transcends beauty, invoking both awe and terror, summoning up dread and trapping the viewer between wonder and anguish.[4]

This sublime nature is the mirror of our times, which, while it amazes us with its progress and achievements, also engenders fear and anxiety due to the multiple crises it faces. The questioning of the Western focus as the sole matrix for understanding the world, the emergence of new discourses and actors with monopolistic or even hegemonic vocations, are all signs that herald an apocalypse, not to be understood as the end of the world, but as the birth of a new world.

In response to these saturated and twilight visions, Buchakjian presents an utterly muted piece on paper. Seen from a distance, it gives the impression of a gray abstraction articulated on two parallel bands set at an angle to the frame. Up close, it appears to reproduce the ground plan of a Roman temple. Ruins are the quintessential Romantic subject. At the end of the 18th century, they were sublimated in Piranesi’s Vedute di Roma and in Hubert Robert’s drawings and paintings. In 1791, Constantin-François Chassebœuf de La Giraudais, known as Volney, published The Ruins, or a Survey on the Revolutions of Empires. The book opens with an invocation of the remains of Palmyra before elaborating a theory of political history.

« I hail you, solitary ruins, sacred tombs, silent walls! It is you whom I invoke; it is to you that I offer my prayer. (…)

O tombs! What virtues you possess! You strike terror into the hearts of tyrants, you taint their impious pleasures with a secret dread; they flee from your incorruptible presence, and the cowards carry the pride of their palaces far away from you. »[5]

While history has unfortunately not proved Volney right, and the tombs and other monuments of Palmyra have been the victims of acts of terror and destruction, we also recognize the emphatic tone that reflects the aesthetics and spirit of the time. None of this emphasis, nor the pathos that also prevailed at the time, shine in Buchakjian’s drawing. Already, the bird’s-eye view, taken from an aircraft, obliterates grandeur to flatten the subject. Even archaeological surveys are more eloquent, highlighting the decayed state of the walls. Here, the latter merge with a heap of stone that saturates the space, all treated with the same nuances, to the detriment of contrasts.

This dull image is set off by another equally dull image that serves as wallpaper. The title, HN051overthe artist’s body, suggests that the drawing covers a self-portrait that is invisible to us unless we dismantle the installation. The title also tells us that the monument in question is the great temple of Hosn Niha, perched on the eastern slope of Mount Sannine, for which “HN51” is the code established by the General Directorate of Antiquities.

The ruin featured on the wallpaper in which Buchakjian is said to have portrayed himself is also in bird’s-eye view. In a rough concrete structure emerge iron elements, cables, breeze-blocks and a disc whose function is indefinable and certainly foreign to the Vitruvian precepts that advocated the use of the circle in the articulation of sacred buildings. There are no visible details to indicate the cause of the disinheritance. In Volney’s time, cities were falling into disuse, while empires were losing their lustre. Since the end of Romanticism and the Industrial Revolution, the pace of change has accelerated. In his description of the Angel of History, Walter Benjamin states that:

“Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”[6]

This memorable text was written between the end of 1939 and the beginning of 1940, in other words, between the outbreak of the Second World War and the author’s suicide. Benjamin had witnessed the rise of totalitarianism but, so to speak, had spared himself that of the Death Camps and the apocalyptic destruction of cities: Warsaw, Rotterdam, Dresden, Hiroshima. Nor did the philosopher witness the military-technological exploits of the following decades, from Napalm in Vietnam to the guided missiles of the Gulf War which, as Baudrillard points out, “never happened”, nor was he able to comment, almost a century later, on the urbicide and genocide perpetrated in the Holy Land in the name of a nuclear power’s presumed right to defend itself.

It’s at Srouji, however, that things get complicated, so much so that the pieces he presents seem to send out contradictory signals. We’re greeted by large-format works whose shimmering colors could be a reference to the romantic seascapes of yesteryear. Far from realism, we are invited to plunge into a visual imaginary of musical composition and contemplate pieces of land, sea and sky, where spaces are intertwined, temporal dimensions altered and the human figure excluded.

At the same time, the eye is drawn to works that are more modest because they are smaller, but also “poorer” as they are practically achrome, not to say stunted. These landscapes are frozen, charred, dismembered, both as representations and as objects, so that the paintings look as if they are about to crumble and disappear forever. Unlike his two colleagues and himself, when he seduces us – or tries to seduce us – with his “beautiful manner”, Srouji here inscribes his practice with an economy of means, as if to show what is not, or what is no longer. One fact is worth mentioning: the artist here integrates the element of fire as an integral tool in his creation. Free canvases, burnt and nailed to the wall. Is Srouji announcing the End of Romanticism through fire?

Fire is already a marking technique; here, it’s a subject that goes back to the journey of the artist, his generation and possibly those that followed, who saw and experienced successive Naqbas hit the country and the region.[7] In other words, being born in this part of the world is synonymous with an obligation to live in uncertainty and chaos, with departure as the only hope of salvation, another romantic idea, where elsewhere would always be better. Twenty years earlier, Samir Kassir wrote that “it’s not good to be an Arab these days. (…) Whichever way you look at it, the picture is bleak, and even bleaker when compared with other parts of the world.”[8]

Since the late 80s of the previous century, Srouji has been attempting to address this troubling question of identity and belonging. Subsequently, he has always flirted with the idea of beauty, expression and emotion, to sublimate real violence. His paintings refer to melodious, dissonant internal structures, as well as to questioning notions of space, composed and recomposed in a temporal and timeless flux.

[1] If a number of ideas and elements of Romanticism reappear in Symbolism at the end of the 19th century, the two movements cannot in any way be confused.

[2] The simulacrum in Plato’s view is thus a deceptive appearance based on an optical illusion. The Stranger introduces this distinction to define the sophist as an illusionist—that is, a producer of simulacra, a fabricator of fictions.

[3] According to Baudrillard, when it comes to postmodern simulation and simulacra: « It is no longer a question of imitation, nor duplication, nor even parody. It is about substituting the signs of the real for the real itself » (« The Precession of Simulacra, » 2).

[4] According to Burke, the Beautiful is what is well-formed and aesthetically pleasing, while the Sublime is what has the power to overwhelm and destroy us.

[5] C. F. Volney. Les Ruines, ou méditation sur les révolutions des empires, Paris, Baudoin frères, 1826, p. 22.

[6] Benjamin, « Theses on the Philosophy of History », Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn, New York: Schocken Books, 1969, p. 249.

[7] The term Naqba or Nakba usually refers to the expulsion of the Palestinian people from their land in 1948. Used in the plural, it returns to its original meaning – catastrophe – to cover all the disasters that have taken place since.

[8] Samir Kassir, Considérations sur le malheur arabe, Arles, Actes Sud / Sindbad, 2004, p. 9.